It was November 1968, and studying the history and culture of non-White groups was still considered a radical idea in the United States. But the students at San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University) and the University of California, Berkeley didn’t back down: For four and a half months, hundreds of students of color went on the longest student strike in U.S. history, calling for the inclusion of people of color in the university curriculum and the establishment of an ethnic studies department on campus. Less than a year later, student protesters arrived at a historic settlement with their schools.

Fast-forward to today. The push for more inclusive curricula in schools has catalyzed a national conversation—rife with conflict and passionate debate—that’s extended beyond higher education and into the K–12 school system.

In March 2021, California approved an ethnic studies curriculum for all K–12 schools; in April, New Jersey passed a new law that requires all public schools to offer courses on diversity and inclusion. Connecticut will require high schools to offer Black and Latino studies starting in fall 2022, and Indiana, Nevada, Oregon, Texas, Vermont, Washington, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have already drafted standards for, authorized, or mandated ethnic courses for schools.

Supporters paving the way for these shifts emphasize that the K–12 curriculum has remained largely Eurocentric, outdated, and disconnected from the growing population of students of color in the United States. Culturally responsive, diverse materials tell a richer, more accurate story that helps all students feel seen and included in their learning, say advocates, who point to research that shows ethnic studies courses can boost students’ academic performance and attendance, as well as helping them develop a better understanding of race, identity, and equity.

“This country is in the middle of a massive identity shift right now: There’s a generational shift happening; there’s a racial shift happening,” says Wayne Au, a professor of critical education theory and educational equity at the University of Washington who has published research and books about racial and social justice teaching. “They’re sort of the birthing pains of trying to decenter whiteness as a country—and ethnic studies is part of the battle.”

Bringing inclusive lessons into classrooms isn’t a straightforward endeavor and raises many questions. Educators around the country have been adding texts and books by authors of color, crafting a framework to teach about tribal nations, and teaching history from the perspectives of different racial groups. But what classifies as ethnic studies? What objective criteria are used to define “ethnic groups,” for example, and who should be drafting the lessons?

WHAT IS ETHNIC STUDIES?

Though the term ethnic studies can feel ambiguous, it generally refers to the teaching of histories, cultures, and intellectual traditions of people of color in the United States to promote social transformation, says Au.

While interest in ethnic studies has been reenergized recently after the murder of George Floyd and the historic protests of 2020, its roots stretch back more than 50 years to the civil rights movement and other tectonic cultural shifts in the 1960s. “Ethnic studies is an academic discipline, but it really is rooted in a movement—a social movement,” says Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, a professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University.

It’s not just about teaching history, explains Tintiangco-Cubales. “It is also about social science, literature, math, all of those things coming together—it’s interdisciplinary.” This means the inclusion of text, film, music, literature, oral histories, research, and scholarship created by people of color and about people of color, she adds.

To create an effective ethnic studies curriculum, proponents like Tintiangco-Cubales say that teachers need to seek out and incorporate voices of people of color who have firsthand experience of the culture and understand the legacy of their group. Teachers should avoid token representation, like focusing on a commonly mentioned or safe historical figure, or relying on short, formulaic paragraphs in a textbook, says Tintiangco-Cubales.

In Texas, for instance, where the Latinx population is growing rapidly, the State Board of Education approved a Mexican American Studies course in 2020, built on the efforts of districts like Houston. The course will expose students to a wide array of content, like the scientific achievements that developed in the Mayan and Aztec civilizations and selected works of Mexican American literature such as I Am Joaquín, by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzáles.

But because not all states have (or will have) ethnic studies courses in their curriculum or make it a graduation requirement, educators can opt to weave the diverse perspectives and stories into existing, standards-aligned lessons, say ethnic studies proponents. Given that rich materials exist online, teachers have far greater access to resources than they did in previous decades. Los Angeles–based high school teacher Guadalupe Carrasco Cardona, for example, posts videos of her ethnic studies lessons on her website, with topics such as Asian Americans in theater and film and a deep dive unit on the book I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter.

“I modify [the content] to whoever is in my class and to what’s going on in the world,” says Cardona, who has taught in California, Arizona, and Texas.

AN ONGOING DEBATE

According to Wayne Au from the University of Washington, carving out a specific space for ethnic studies, and naming it as such, sends an important signal that Eurocentric knowledge is not the basis of the world’s knowledge and provides educators with concrete, practical language to advocate for culturally responsive teaching.

“If the world were right, we wouldn’t have to name it ethnic studies because then we would be doing it in all of our teaching,” says Au.

But to others, there’s debate over what does and doesn’t constitute ethnic studies, what it should be called, and how educators should implement it.

“When you mention ethnic studies, it just really gives me pause, it kind of jars me,” says Yvette Jordan, who has taught history at Central High School in Newark, New Jersey for 15 years. Jordan, who is Black, explains that she has always taught in a way that takes into account diverse perspectives, which helps students understand the confluence of those voices and gives them the opportunity to formulate their own opinions.

“When you do that, you’re not teaching ethnic studies—you’re just teaching,” she says. “I wouldn’t think of teaching in any other way.”

To some teachers, determining what groups should be included under the term ethnic studies presents another point of contention.

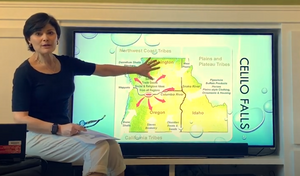

Courtesy of Shana Brown

Shana Brown, a Yakama and Muckleshoot teacher and curriculum specialist, and Gail Morris, Nuu-chah-nulth Native American education program manager, say that it’s a misnomer to put Native American studies under ethnic studies because Native Americans aren’t an ethnic group or a singular identity in the United States—they are 574 unique nations. The teachers, who both work for Seattle Public Schools, have been assisting the state of Washington, the National Park Service, and the National Museum of the American Indian to develop materials that help people understand the crucial but often neglected role of Native Americans in U.S. history.

“When we look at the history of the United States of America, we are U.S. history,” says Morris. “U.S. history doesn’t begin with Plymouth Rock; it doesn’t begin with Lewis and Clark; it begins with us.”

Around the country, efforts to adopt ethnic studies curriculum—or just make lessons more culturally inclusive—have also encountered pushback. Recent bills, for example, would ban critical race theory in public schools in Idaho or prohibit teachers from receiving training or discussing racism and sexism in Texas classrooms. And in California, even though the curriculum was adopted, many ethnic studies proponents were the ones displeased.

According to Cardona, the curriculum approved by the state was not a “model curriculum” but a watered-down version of what the writers had proposed that disregarded the perspectives of people from the ethnic groups themselves.

“By decentering the voices of the communities themselves, [it is] no longer ethnic studies, because that’s what is calling for—for those groups to be the ones that decide what the curriculum is,” explains Cardona, who says she and other writers asked to have their names removed from the curriculum.

DOING IT RIGHT

While ethnic studies has garnered more public attention recently, many teachers in places like Tucson, Seattle, and San Francisco have been successfully teaching a more inclusive curriculum for years and can serve as guideposts for other schools, says Au.

As someone who has been teaching ethnic studies and social studies for 20 years in different states, Cardona says she has learned to make her lessons work within the constraints of state standards by seeking out other texts on the same subject to give students a more robust perspective of that time in history.

Yvette Jordan, meanwhile, says she teaches history through various lenses. When learning about the Reconstruction Era, for example, her students learn about how Black people were feeling at the time as newly freed people, why White people were angry, and how White women were asking the question of why Black men got to vote but they couldn’t.

And in the case of Native American Studies, educator Shana Brown and others set out to write a general framework that could be adapted to regional histories of different tribes and districts. In a unit about tribal government, for example, Brown developed a set of guidelines, such as talking about the structure and impacts of the relationships between tribal governments and the U.S. government.

According to Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, adapting curriculum can greatly impact teachers too.

“When teachers go through ethnic studies teacher development, they are likely to be much more connected to their community or the communities that they’re serving,” she says. “They’ve been able to develop strong, lasting relationships. They’re often more critically conscious, more empathetic to students, and they usually focus more on strength-based pedagogy.”